The Thai-Myanmar Border Studio continues ten years of design-based experiential learning in mainland Southeast Asia for our undergrads in HKU's Division of Landscape Architecture. Landscape students spend one term engaging large-scale development problems via landscape architecture and landscape planning. During the studio, students develop and present a 100-page research report to civil society, visit a diverse range of development projects and programmes across northern Thailand, individually design strategic planning proposals, and have their work juried by a panel of experts from planning, sociology, ecology, and geography.

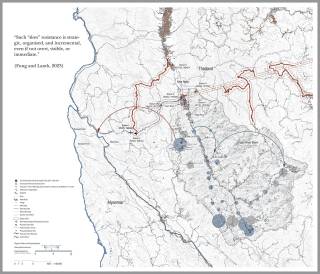

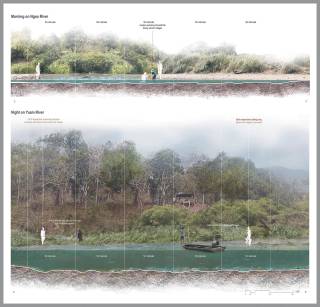

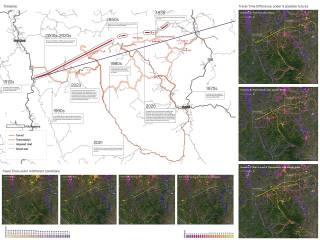

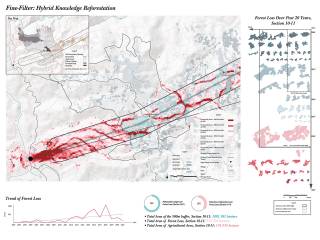

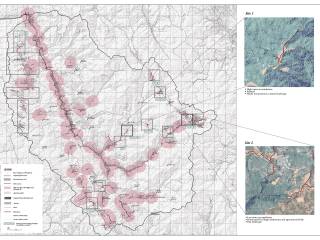

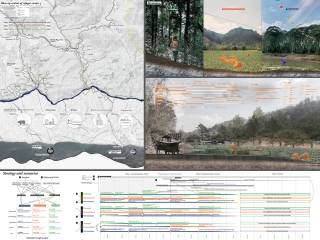

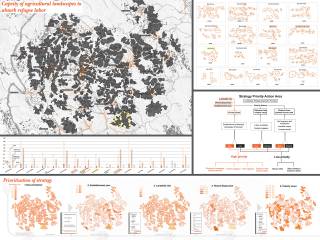

This year, students focused on a set of controversial and long-delayed development projects along the Thailand-Myanmar border, including dams on the Salween and Yuam rivers, a coal mine concession in Chiang Mai province, industrial zones in Mae Sot, and the planned large-scale water diversion tunnel from the Salween to Chao Phraya basins. For 10 days in mid-March we traveled from Chiang Mai to Mae Sot, meeting with several environmental and human rights advocacy groups, including International Rivers, The Border Consortium (TBC), Karen Environmental and Social Action Network (KESAN), EarthRights International (ERI), and indigenous community groups.

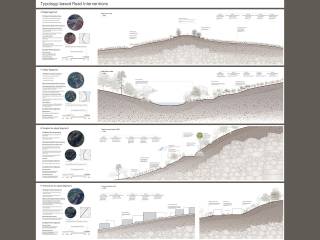

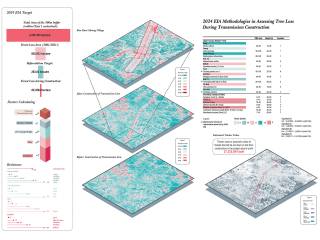

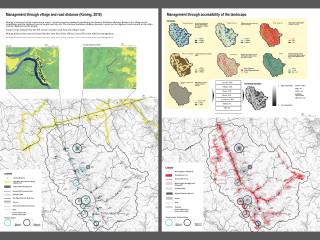

Since the start of the pandemic in 2020, civil society across Thailand and Myanmar (and elsewhere in Southeast Asia) has been greatly constrained, most notably in their capacities to monitor development projects due to (1) restrictions on movement and (2) investment withdrawal and project reorganization that has led to a significant backsliding of environmental and social safeguards. Nearly all development advocacy work, both environmental and humanitarian, has come to a halt in Myanmar. Many projects that had been stalled pre-pandemic are now moving forward given these weakened safeguards. Such protracted projects use years- (and sometimes decades-) old feasibility studies and environmental impact assessments (EIA) while simultaneously undergoing project restructuring that results in both accidental and purposeful breaks or discontinuities in environmental knowledge. Such protracted development projects are also challenged with integrating, subsuming, or resisting newer forms of environmental knowledge (e.g., predictive ecological models, citizen science, participatory GIS) coming from the state, NGOs, and organized civil society. Further, few projects consider the cumulative impact of plans that fail to materialize or that continue for long periods in various stages or cycles of protracted planning, design, and preliminary construction.

Civil engineers, planners, and landscape architects (as, e.g., road ecologists, landscape ecologists, master planners, and the professionals undertaking visual impact assessment in EIAs) work on various components of the feasibility, planning, design, implementation, and monitoring of development. These professionals are the teams with expertise capable of assessing cumulative impact, yet these teams instead frequently reproduce discontinuities in the environmental knowledge of large-scale physical infrastructure projects. This studio tasks students to be critically reflective on how they assemble environmental knowledge and propose interventions in regional planning and infrastructure development.